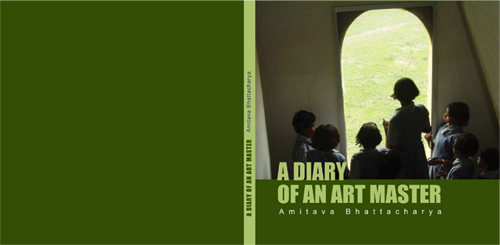

Download (pdf) “A Diary of an Art Master” by Amitava Bhattacharya

Art Master Diary: Indigenous Creativity and the Power of Imagination

by John Clammer

The source of positive social change is not economics or politics in the last analysis – it is creativity and imagination. The possibility of envisaging another world is the root of the future. Decades of “development” in India and throughout much of the world have not brought about the benefits promised. Poverty, deprivation and marginalization continue and in many cases increase. The experience of development for many has been one of violence, not of a peaceful transition to a richer, more secure, healthier and happier world.

This very negative form of development has tragically been the fate of many of the Adivasi communities in India, and not of these alone: many Dalit and other socially marginalized communities have had similar experiences – at the worst loss of land to mining, dams and other mega-projects, at best continuing poverty, lack of access to healthcare and education and very little participation in the “Shining India” promised by the political and economic leadership. But despite this, the experiences recorded in this diary of Amitava Bhattachcharya’s fertile attempt to introduce art to the children of remote villages in Madhya Pradesh shows, as we might expect if not blinded by caste-ism, and social and cultural prejudices about the poor and rural life, that behind the deprivation lies a whole continent of humanity: of creativity, close links to nature, of warmth, humour, hope and imagination, simply waiting to be released.

Studies elsewhere have shown that in working with excluded communities and individuals – the mentally handicapped, slum dwellers, victims of trauma – art often proves to be a liberating force, not only allowing a non-verbal means of self expression, but revealing to those who try it that they too have resources of creativity that they may never have imagined. That discovery is itself empowering, and one very good thing about such “art therapy” is that it is non-competitive: no one is striving to be “better” than others, all that is important is that experience is expressed and given a concrete form that allows both the self and others viewing the art a means to come to terms with the life experiences that it embodies. So it is in the villages that formed the location of Amitava Bhattacharya’s experiment in teaching art, or rather perhaps in providing the opportunity, materials and incentive for children to discover the artist latent in themselves.

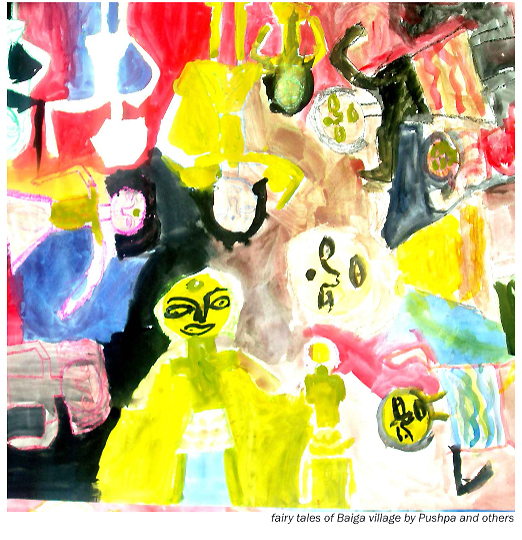

Many significant lessons are to be derived from the “Art Master’s Diary”. Anthropologists concerned with development have recently begun to discover what they are calling “Indigenous Knowledge” – usually practices of medicine, agriculture, fishing and survival. But almost always the conception of such indigenous knowledge is highly cognitive – it rarely extends to the perception that the imaginative and creative life of peoples is also a significant part of their total body of knowledge. Yet here in these remote villages we find that this is very far from true – not only is there indeed a local knowledge of such essential things as agricultural techniques, but there is also an alternative aesthetics, arts and crafts rooted in nature and daily experience and utilizing local materials in an organic and sustainable way, but also a strong predilection or stories. Many studies, both in literary scholarship and in the sociology of medicine have shown how important narratives are for any culture and individual to make sense of experience, to create a framework for understanding what is happening and to link these current events to tradition. In the paintings produced by these village children, we see immediately how true this is: stories are strength and give the community a means of engaging with the world while retaining the core elements of their own culture.

Bhattacharya notes how the Russian-Jewish painter Marc Chagall drew much of his inspiration from both nature and folk tales, and from the intimate life of the ghetto communities in which many Russian Jews lived at the time. The same of course is true in Indian art – immediately one thinks of Jamini Roy, and of the Indo-Hungarian painter Amrita Sher-Gil and the latter’s settling in and depicting the everyday life of the village of Saraya in the Gorakhpur district of Uttar Pradesh. But these were depictions from without: the work shown in this diary however is from within – from artistically untutored children who given the materials and the occasion, immediately began to produce vivid paintings, glass art and murals, drawing instinctively on their environment, culture and experiences and depicting both the realities of everyday life – the search for water and food, but also its joys and especially dancing and the festivals that punctuate their lives of labour.

Amitava, the Art Master

But at the same time the diary raises questions of another level. Some of these concern the role of the professional artist in such a situation: is his or her position one of essentially extending personal vision (as perhaps was the case with Sher-Gil), or is it to help extend their vision, that of the individuals and communities experiencing these new expressive possibilities? Of course the artist is bound to take away all sorts of new themes and inspiration from such an intense experience, but the much more valuable aspect of the work embodied in this diary is certainly the latter aspect – to promote forms of creativity that while in this case rooted in visual art, might potentially lead to new cultural and civilizational forms that will help these communities transcend feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. Other issues concern the dangers of assimilating these newly discovered forms of artistic creativity to the “art world”, as has happened to a great extent with Australian Aboriginal art or even the Pat paintings of Bihar and West Bengal, that have in many cases become commodified and certain “star” artists identified at the expense of the originally communal and democratic forms of art production.

A big issue here then is ultimately what new forms of development are possible? Amartya Sen has famously defined development as freedom, and if this freedom is to be inclusive it must include freedom of the imagination, and of creativity located in a field of social and economic justice. The communities represented here stand as a kind of case study of possibilities: of how indeed to locate these indigenous imaginative and expressive resources in a context that will empower them, and not simply enrich others who would exploit them or turn their art into just another commodity in the art market. It is the responsibility of the larger art world indeed not to exploit, but to nurture such expressions and to see that they flow back to the benefit of the creative but desperately needy communities that have produced them. It is evident from the Diary that huge internal resources for change and empowerment, of promoting gender equality and of self expression exist in these villages, seemingly cut off from the mainstream of development and indeed in many respects its victims. Paradoxically this may be their salvation: to pioneer new forms of imaginative futures that makes them part of a wider solidarity economy that will withstand the huge crises that the mainstream economy is going to face as it comes up against declining oil and other resources.

Self-esteem is the basis of change: what the Diary show so clearly is how that can be achieved, not through traditional competitive education, but by liberating the springs of creativity. Aravind Adiga, the author of the prize-winning novel The White Tiger suggests in that book that artistic creativity lies at the basis of a social revolution, or as he puts it in his more earthy language “ Iqbal, that great poet, was so right. The moment you recognize what is beautiful in this world, you stop being a slave. To hell with the Naxals and their guns shipped from China. If you taught every poor boy how to paint, that would be the end of the rich in India”. As Bhattacharya’s initiative shows, all that has stopped the children in the villages where he worked was an invitation to creativity. None of them had been encouraged to express their artistic sensibilities and none had ever worked with these media – water colours, paper, glass, before. But once given the “permission” to do so, their autonomy as creative individuals immediately shone through. Here indeed is the basis of a cultural revolution: the liberation of the imagination.

Perhaps we can close with the words of the great philosopher John Dewey, who amongst the many subjects, philosophical and political, that engaged his attention, was that of art. In his work Art as Experience he said the following: “Imagination is the chief instrument of the good…art is more moral than moralities. For the latter are, or tend to become, consecrations of the status quo, reflections of customs, reinforcements of the established order. The moral prophets of humanity have always been poets even though they spoke in free verse or by parable…Art has been the means of keeping alive the sense of purposes that outrun the evidence and of meanings that transcend indurated habit”. In the isolated villages of Chattisgarh district we see the truth of this: the seeds of transformation, self-respect and empowerment growing from the simple act of allowing children to see anew and to express that seeing in colour and image.

Download (pdf) “A Diary of an Art Master” by Amitava Bhattacharya